INTERWEAVING

2021-2022

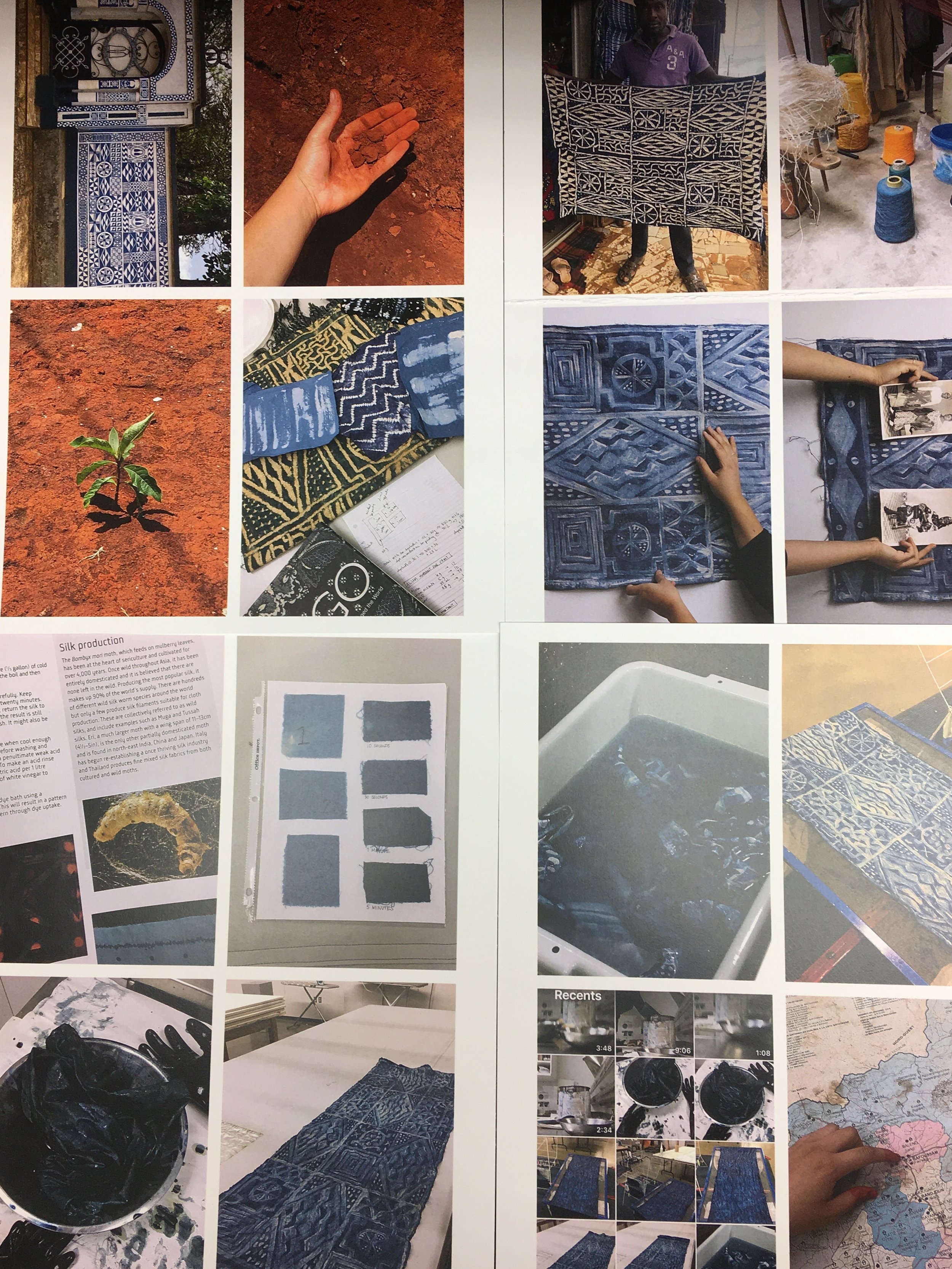

Interweaving exploress Ndop cloth indigo tradition and symbolism while drawing connections to European denim (indigo dyed) culture from the 19th century.

“At Senegal’s Dak’Art 2022, the Biennale of Contemporary African Art — one of the longest running biennales on the continent — Mpoka presented her artistic research in dialogue with Oslo-based queer textile artist Damien Ajavon. Together, their collaborative installation Espace-Temps (2022) for the Off-Satellite program, curated by Senegalese textile artist Aïssa Dione, takes the form of an artisanal workshop tucked into a corner of Galerie Atiss Dakar.

Mpoka explores the material and cultural histories of Ndop cloth — an indigo resist dyed textile with such deep cultural significance that it was recently classified as a Cameroonian national heritage—while tracing connections to nineteenth-century European denim. In Interweaving, a five-metre textile piece with a repeating pattern of rectangles is poised in a sewing machine on an artisan’s bench in the centre of the tableau vivant. Alongside, spools of thread line the wall. Interweaving ancestral African and diasporic knowledges, Mpoka incorporates water-based batik and couture sewing with rich geometric and figurative Ndop symbolism, her knowledge of which comes through her ongoing personal research as well as exchanges, during her summer residency at Jean-Félicien Gacha Foundation, with traditional Cameroonian knowledge holder Idrissou Njoya, personal artisan of the king in the Foumban chiefdom. For the Bamileke people, indigo is not only the colour of the sky but also that of nobility, the supernatural, and the ancestors.6 Signifying wealth, abundance, and fertility, and asserting royal status in the Grasslands kingdoms, Ndop textiles—much like family photographs—are a significant part of family heritage.

Reflecting on family and cultural heritage while subtly interrogating the imbrication of racial capitalism in the material histories of trade, Mpoka’s installation aims to both preserve and reinterpret this ancestral textile practice. Rather than working with the traditional hand-dyed cotton, Mpoka takes as her raw material Europe’s discarded textiles, which have their own diasporic stories to tell. Like Walter Benjamin’s ragpicker, she collects second-hand denim from shops in the Douala Market, close to her uncle’s handbag workshop. The streets surrounding the market are continually transformed by ephemeral mountains of clothes spit out by the Western fashion industry. In Kenya, these clothes are called mitumba (bundles); in Ghana, they are called obroni wawu (dead white men’s clothes). In Espace-Temps, Mpoka weaves the refuse—of photography and fabrics—into haptic assemblages that critically engage the transnational trajectories of the garment industry while reimagining the possibilities of Black futurity across the diaspora.

Responding to the movement of diasporic knowledge, exchange networks, and colonial entanglements, Mpoka’s installation alludes to the intertwined history of blue jeans, indigo, and the transatlantic slave trade. Indigo-dyed denim has roots in seventeenth-century Genoa, Italy, where waxed work pants were produced, and in Nimes, France, from where it takes its contracted name (de Nîmes). But it was enslaved Africans who carried the vernacular knowledge of indigo to the United States, where they transformed it into dye on plantations through a complex process involving fermentation. By intervening in this “botanical conflict,” Mpoka’s haptic engagements with ancestral craft knowledge invoke the political histories and anticolonial struggles focused around soil.”

Gwynne Fulton, Esse Magazine Issue 107